Bridges, Not Primitives

Why DeSci should stop searching for universal verification and start building compositional translations.

Introduction

Here’s a problem nobody talks about enough in decentralized science: how do you get a biologist and a physicist to collaborate without someone eventually muttering “well, actually, it’s all just atoms” and the other person leaving the room?

This isn’t a joke (well, it kind of is but whatever). The history of interdisciplinary science is littered with promising collaborations that collapsed because one field’s way of verifying truth felt like an insult to another’s. The physicist thinks the biologist is being sloppy. The biologist thinks the physicist is missing the point. Both are, in a sense, correct—they’re just operating at different causal grains, and neither has a language for saying that without it sounding like a concession.

Now multiply this across every field boundary, and you start to see the challenge facing decentralized science. Molecule creates IP-NFTs for biotech research. ResearchHub builds tokenized peer review with reputation systems. VitaDAO pools funding for longevity research through community governance. DeSci Labs develops IPFS-based research objects. The work is promising and underneath much of it runs an assumption: that if we build the right general infrastructure, verification will converge toward a unified system.

What if that’s the wrong goal? What if trying to build universal verification is precisely what causes the biologist to leave the room?

Erik Hoel’s work on causal emergence suggests something worth considering: different levels of description can carry different amounts of causal information. Sometimes the coarse-grained picture is more predictive than the fine-grained one. The biologist’s “sloppy” macro-level reasoning might actually be the right grain for the causal structure they’re studying. Physics verification works for physics because physics operates where five-sigma precision is achievable and meaningful. It’s not that one is more rigorous—they’re adapted to different territory.

This points toward a locality principle for knowledge. Each domain has developed its verification structures for good reasons. They’re tuned to what that field has learned to care about. If we build infrastructure that respects this locality—that formalizes each domain on its own terms and then looks for structure-preserving maps between them—we can capture all the information. If we force everything through universal primitives, we lose exactly what makes each domain’s standards work.

There’s a tradition in applied mathematics that does precisely this, applied category theory. Rather than searching for universal foundations, you formalize each domain’s structure and look for bridges that preserve what matters when you translate. The question shifts: not how to flatten differences, but how to connect local structures—and how to know when a bridge is actually working.

What might that offer DeSci? When you look at the same phenomenon through different lenses, sometimes both paths converge. When they do, you’ve found something robust—verification from multiple directions. When they don’t, you’ve found exactly where something is missing.

And if the epistemology doesn’t convince you, consider the social benefits: you could become the patron saint of interdisciplinary collaboration. The one who finally built infrastructure where biologists and physicists can work together without the physicist eventually saying “but fundamentally...” and the biologist suddenly remembering an urgent appointment elsewhere. You respect what each field knows. You build the bridges. Everyone stays in the room. Nobody cries.

Representing Salt

I was discussing knowledge representation with my dad and I wanted to point out how different descriptions can get to the same target with differing levels of underlying complexity. This is the argument I made the poor man go through:

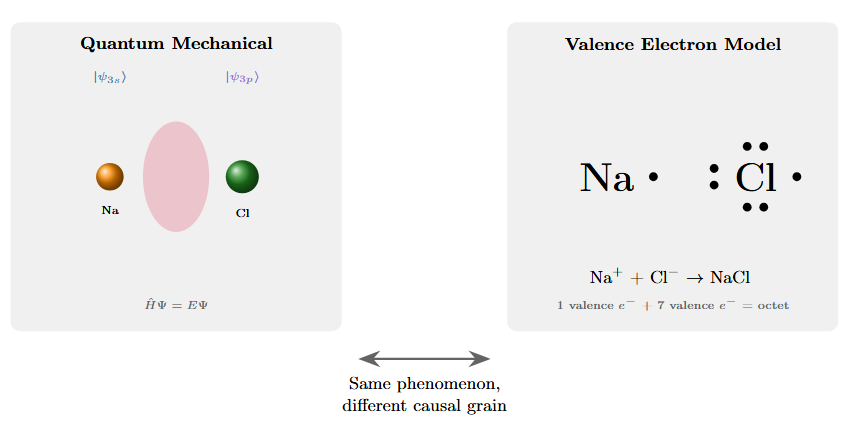

I could explain quantum chromodynamics unified with electrodynamics, work through the Schrödinger wave equations that govern electron probability clouds, trace the dependency relations between atomic orbitals, and eventually arrive at the electromagnetic forces that bind sodium to chlorine in a crystal lattice. This would be precise. It would also be a bunch of work for nothing. Why? Because there’s an easier way of representing it.

I could also say: sodium has one extra valence electron it wants to get rid of, chlorine is missing one, they share, and now you have salt. This description throws away almost everything about the underlying physics. And yet it tells you more about what will happen.

Figure 1: Two representations of sodium chloride bonding. Left: electron density probability clouds from quantum mechanical treatment, showing complex overlapping orbitals and wave function interactions. Right: Lewis dot structure showing valence electron transfer. The simpler representation isn’t an approximation—it captures the causal structure that matters at the chemical scale with higher effective information for predicting bonding behavior.

One could say that the electrodynamics based model is more true since we have higher sigma for our outcomes yet from an information theoretic perspective that’s not necessarily true. It’s not that valence electron chemistry is a degraded version of quantum field theory, acceptable only when we lack computational resources for the real thing. The valence description captures exactly the degrees of freedom that matter for predicting molecular behavior and discards the ones that don’t.

Now if I was running a weird experiment on something like Bose-Einstein Condensate, the non quantum-mechanical model wouldn’t hold. But if I wanted to break a salt crystal apart, it probably would.

The same pattern appears with gases. Under conditions approaching the ideal, PV=nRT tells you what you need to know. You don’t need the full Boltzmann distribution of molecular velocities, the Maxwell speed distribution, or the detailed collision dynamics. The macroscopic variables—pressure, volume, temperature—are the right causal grain for that regime. But drop to very low pressures or push to extreme temperatures, and suddenly the molecular details start mattering again. The ideal gas law breaks down not because it was ever wrong, but because you’ve moved to a regime where a different causal grain becomes appropriate.

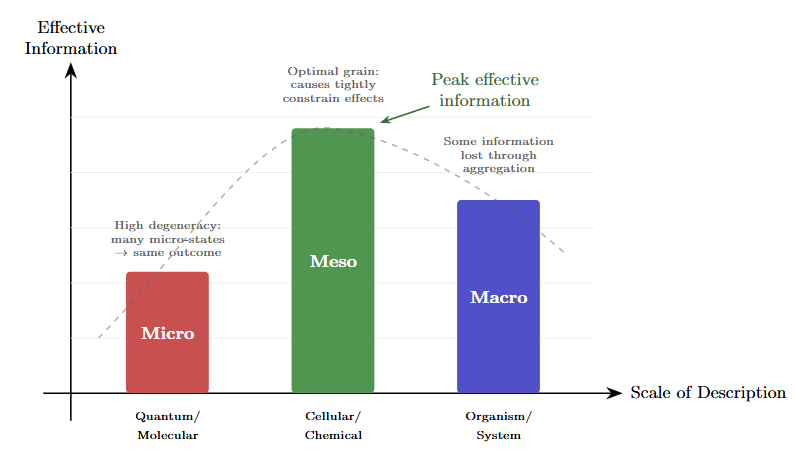

This observation has a name now, thanks to work by Erik Hoel and collaborators on what they call causal emergence (Hoel, Albantakis & Tononi, 2013). The technical measure is effective information: how tightly does knowing the cause constrain the effect?

The counterintuitive finding is that coarse-grained, higher-level descriptions can have more effective information than fine-grained, lower-level descriptions of the same system (Hoel, 2017). The macro isn’t always a blurry approximation of the micro. Sometimes it’s a sharper picture.

Figure 2: Effective information across scales. Different levels of description have different amounts of effective information—the degree to which knowing the cause constrains the effect. The peak occurs where the descriptive grain matches the natural causal grain of the phenomenon.

If we take this perspective of information at different scales being differently useful in different fields we can start to see the shape of an answer to why knowledge verification is represented differently. Physics can demand five-sigma because it’s looking for universal regularities with high signal-to-noise. Psychology’s replication crisis happened because the field was using methods calibrated for a different signal-to-noise ratio than human behavior has. Medicine’s evidence hierarchy acknowledges that clinical decisions require explicit uncertainty tracking across multiple levels of evidence quality.

Different fields adapted to different causal grains.

Why Different Scales Need Different Atoms

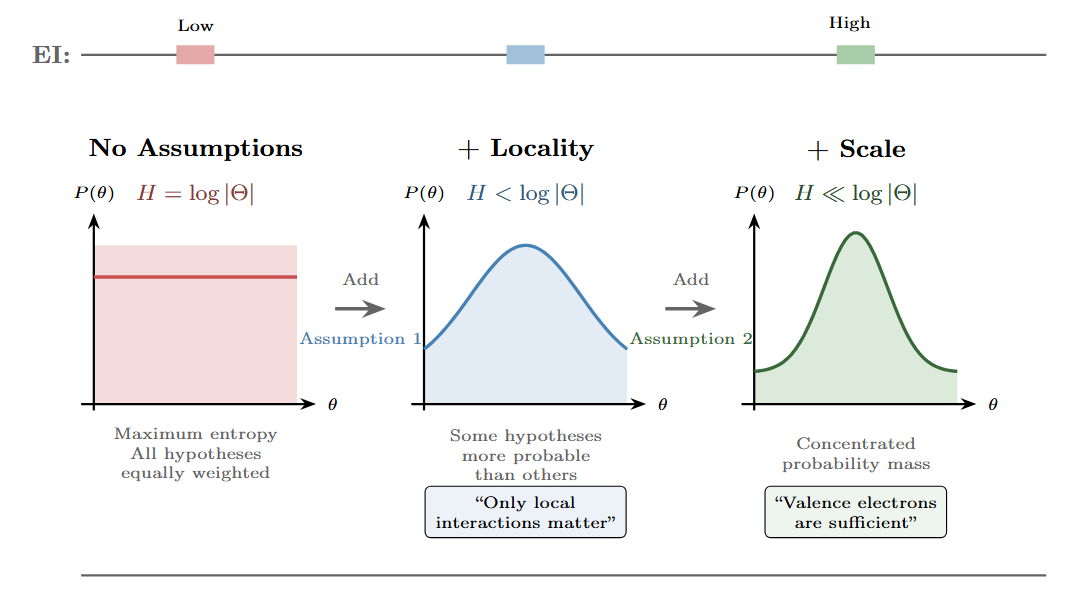

We can think of choosing a level of description as making assumptions that constrain our hypothesis space. Before you commit to a level of description, all scales are equivalent—you could describe the system at any grain. When you choose the valence electron representation over the quantum field theory representation, you’re making a commitment about which degrees of freedom matter.

Figure 3: Assumptions constrain the probability space. Reading left to right: starting from maximum entropy (uniform prior over all hypotheses), each assumption narrows the probability distribution over possible descriptions. The first assumption (locality) rules out non-local interactions. The second (appropriate scale) focuses on valence electrons rather than full quantum states. Counterintuitively, the most constrained distribution—with the lowest entropy—has the highest effective information for predicting chemical bonding.

The valence electron description implicitly encodes a prior that says: “the detailed electron orbital configurations don’t matter; only the count of valence electrons matters.” This prior throws away information, but it throws away the right information—the information that doesn’t help predict chemical behavior.

Stuart Kauffman’s adjacent possible reframes how we should think about knowledge infrastructure (Kauffman, 1993). The dream of universal verification assumes knowledge is a single space with uniform structure—build the right protocol and it works everywhere. Kauffman’s picture is different (Kauffman, 2000). Knowledge space is locally structured. What counts as a valid move, a good explanation, a convincing verification—these depend on where you’re standing. The adjacent possible isn’t defined globally; it’s defined relative to your current position.

This matters for DeSci because it reframes what verification protocols are. A protocol isn’t a neutral measurement instrument. It’s a commitment about what counts as signal versus noise in a particular region of knowledge space. Physics chose five-sigma because that prior matches the causal structure of particle physics—rare events against well-characterized backgrounds. Psychology’s p < 0.05 and subsequent reforms are attempts to find priors that match human behavioral research, where effect sizes are smaller and variability is intrinsic. Medicine’s GRADE hierarchy is a prior about how different study designs relate to clinical truth.

Brain development offers a useful analogy for what’s happening here. The brain doesn’t maximize connectivity—it prunes it. Early development involves massive overproduction of synapses, followed by systematic elimination. The mature brain is sparser than the infant brain, not denser. This seems backwards until you realize what pruning accomplishes: an unpruned network refuses to make commitments. Every input is potentially relevant to every computation. There’s no structure, no specialization, no efficiency. A pruned network has decided which inputs matter for which outputs.

Each pruned synapse is a prior: this signal doesn’t matter for this computation. The pruning is what creates high effective information. By committing to what matters locally, the network becomes sharper, more predictive, more useful—even though it’s “thrown away” most of its connections.

A universal verification protocol is an unpruned network. It refuses to commit to what matters where. It treats every possible signal as potentially relevant to every possible claim. Domain-specific protocols are pruned networks—they’ve made commitments appropriate to their region of knowledge space. Physics verification has pruned away the variability that dominates social science. Medical evidence hierarchies have pruned in ways that track what predicts clinical outcomes.

The process operates near self-organized criticality—the edge between order and chaos. Too many commitments and you’re frozen, unable to incorporate genuine novelty. Too few and you’re noise, unable to distinguish signal from chaos. The critical point is where effective information peaks: enough pruning to transmit what matters, enough remaining connectivity to stay responsive.

Kauffman puts it nicely in an interview that echoes Stephen Wolfram’s bounded observers and Chris Fields’ physics as information processing: we only ever have local views. There’s no god’s-eye perspective on knowledge space. If you’re building DeSci infrastructure that assumes one—universal protocols, shared primitives, one verification system to rule them all—you might be building for a world that doesn’t quite exist.

Getting Concrete

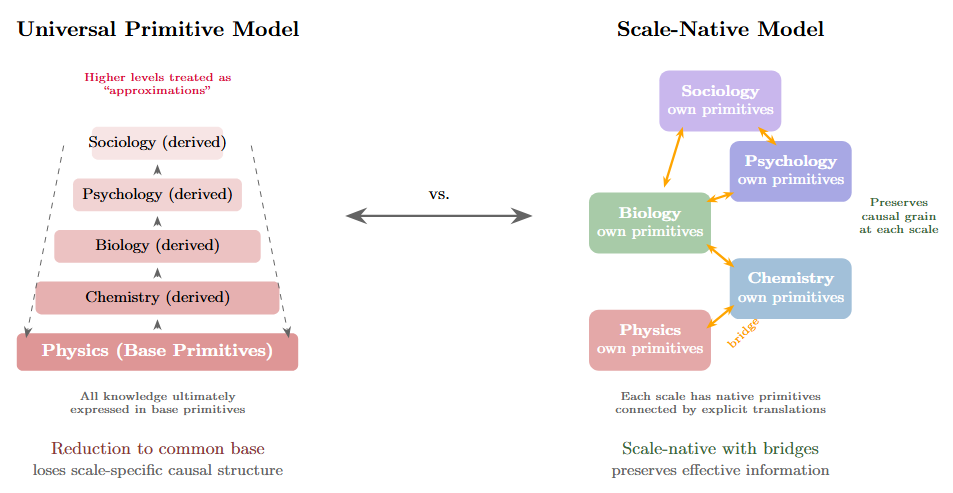

The universal primitive approach probably won’t scale the way we’d hope. Knowledge is heterogeneous. Causation is heterogeneous. Forcing everything through a common substrate tends to destroy exactly the information that matters at each scale.

Figure 4: Two architectures for knowledge representation. Left: the Universal Primitive model assumes a single base layer (physics) with successive approximation layers stacked above, all ultimately grounded in shared primitives. This treats higher-level descriptions as degraded versions of fundamental descriptions. Right: the Scale-Native model treats each level as having its own appropriate primitives, connected by explicit bridge functions that translate between adjacent scales. This architecture preserves the causal grain appropriate to each level rather than forcing reduction to a common substrate.

So what should you build instead?

The Two Objects

Here’s a useful way to think about it. Fields have different verification structures because they study different things at different causal grains. Physics demands five-sigma because it’s measuring universal regularities with high signal-to-noise. Psychology uses different thresholds because human behavior has different statistical structure. Medicine developed evidence hierarchies because clinical decisions require explicit uncertainty tracking.

These differences aren’t arbitrary—they’re downstream of what each field is actually studying.

This gives you two objects to work with: primitives (what a field studies) and verification (how it confirms claims about those primitives). They’re coupled. Map one, you can map the other.

How to bridge fields

There’s a tradition in mathematics that’s been quietly solving this kind of problem for about a century. It’s called category theory, and it’s less scary than it sounds.

The basic move: instead of looking for universal foundations that everything reduces to, you do something different. You formalize the structure of each domain—what objects exist, what relationships hold between them, what operations are valid—and then you look for structure-preserving maps between domains.

A category is just a formal description of a domain: its objects, its relationships (called morphisms), and how those relationships compose. A functor is a map between categories that preserves structure—if A relates to B in one domain, their images relate in the same way in the other.

That’s it. That’s the core idea. Let’s see what it looks like when you apply it to something real.

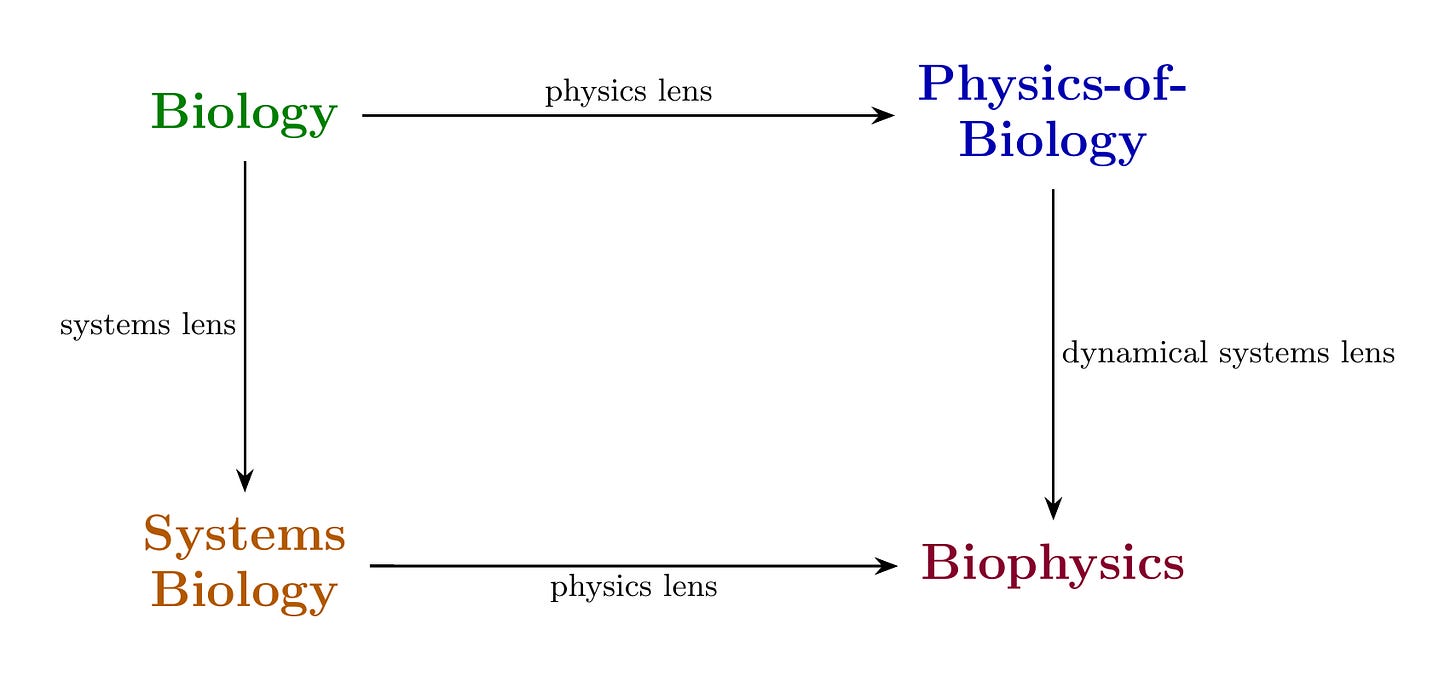

The diagram above is a commutative diagram of biophysics. I could explain this using words like “functorial mappings between epistemic categories” and “morphism-preserving transformations across verification regimes,” but then you’d stop reading and I’d be sad. So let’s just walk through it.

The premise of biophysics is that you can look at biology through physics. You take a cell and ask: what can I actually measure? Voltages across membranes. Mechanical forces on the cytoskeleton. Concentrations of molecules. Energy budgets. This translation—biology seen through physics—gives you Physics-of-Biology. You’ve moved from “the cell divides” to “the membrane potential changes from -70mV to -20mV, triggering calcium influx at rate k.” Same cell. Now with numbers.

The verification structure changes when you apply this lens. Biology tolerates natural variation—cells are noisy, organisms differ, and biologists have made their peace with this. Physics demands quantitative precision. Is your measurement calibrated? What’s the uncertainty? Can someone in a different lab get the same number? When you pick up the physics lens, you inherit physics’ standards for what counts as evidence. The lens comes with rules. You don’t get to negotiate.

You can also look at biology through systems. Same cell, different question: what are the components and how do they interact? Gene regulatory networks. Signaling pathways. Feedback loops. This translation gives you Systems Biology. Now “the cell divides” becomes “the CDK-cyclin network crosses a bifurcation threshold.” If that sentence means nothing to you, don’t worry—the point is just that it’s a different language for the same cell doing the same thing.

This lens has its own verification structure. Uri Alon’s Introduction to Systems Biology makes this explicit: does your network motif appear more often than chance? Does your model predict the response time? If you knock out a node, does the system behave as the model predicts? The questions are about network topology and dynamical behavior, not physical precision. Different lens, different exam.

Consider what happens when you simulate peptide folding, as in origin-of-life research. You could simulate at full atomic detail—every atom, every bond, every quantum wiggle. This would be very impressive and also take longer than you will be alive. So you coarse-grain: you represent groups of atoms as single beads, you average over fast motions, you simplify.

The choice of coarse-graining scale is itself a translation. Different scales preserve different properties. Too fine and your simulation runs until the heat death of the universe. Too coarse and you lose the behavior you actually care about. A friend who does this work describes finding the right scale as an “art”—which is scientist-speak for “we don’t have a formula, you just have to develop taste.”

This is functorial thinking without the jargon. Every choice of how to look at a system—physics lens, systems lens, coarse-graining scale—is a translation that transforms both what you can see and how you verify it.

Now look at the diagram again. There are two paths from Biology to Biophysics:

Path 1: Biology → Physics-of-Biology → Biophysics. You measure physical quantities in a biological system, then ask how those quantities evolve dynamically. You get equations of motion, attractors, stability analysis.

Path 2: Biology → Systems Biology → Biophysics. You identify the network structure, then ask what physical mechanisms implement it. You get circuit dynamics grounded in physical reality.

Do these paths arrive at the same place?

When they do, something lovely happens. You don’t have verification from just one domain—you have it from two. Michael Levin’s work on bioelectricity exemplifies this. He measures physical quantities (voltage patterns across tissues) and he models network dynamics (how voltage states propagate and stabilize). When the physical measurements and the network models agree—when manipulating the voltage produces exactly the pattern the model predicts—both paths converge. The biophysics is coherent. Two different ways of looking, same answer. That’s worth trusting.

When they don’t converge, you’ve learned something specific. Maybe your physical measurements missed a relevant variable. Maybe your network model left out a crucial feedback loop. Maybe your coarse-graining threw away something that mattered. It’s like two friends giving you directions to the same restaurant and you end up in different neighborhoods—someone turned left when they should have turned right, and now you know to figure out where.

Bridging and Generation

So what does all this actually give you?

Two things, mainly. First, cross-field verification. The lenses tell you how verification structures should transform. If you know what counts as evidence in biology and you know the mapping to physics, you can derive what the combined standard should look like. When Michael Levin publishes a biophysics paper, reviewers check both the physical measurements and the dynamical predictions—because the field has learned that convergence from multiple paths is worth more than precision from just one.

Second, cross-field generation. When you make the translations explicit, you start to see where new connections might exist. What’s the systems lens applied to ecology? What’s the physics lens applied to economic networks? The diagrams become maps for exploration—not because the math forces discoveries, but because it shows you where paths might meet that no one has checked yet.

This is, in a sense, what mathematics has always been about. Finding the translations. Building the bridges. Noticing that two problems that looked completely different are secretly the same problem wearing different hats. The Topos Institute is building infrastructure for exactly this—their AlgebraicJulia ecosystem lets you represent scientific models categorically and actually compute whether proposed translations preserve what they should. It’s the difference between saying “I think these are related” and being able to check.

This also connects to work on collective intelligence. Pol.is, Audrey Tang, and the Collective Intelligence Project build bridging algorithms for opinions—finding where different groups actually agree, surfacing consensus that was invisible from any single viewpoint. Scientific composition is the same problem in a different domain. Pol.is bridges in opinion space: where do different viewpoints converge? Compositional methods bridge in structure space: where do different descriptions of the same phenomenon converge?

If you’ve ever been to NeurIPS, you know what happens without these bridges. You’re presenting your biomedical imaging paper, and someone from the deep learning crowd excitedly tells you they’ve invented a revolutionary new architecture that—wait for it—is a convolutional filter. Which signal processing figured out in the 1960s. Or you watch a machine learning paper reinvent Kalman filters, call them “recurrent Bayesian state estimators,” and get cited three thousand times. Meanwhile, the control theory people are quietly drinking in the corner, wondering if they should say something or just let it happen again.

This isn’t anyone’s fault. Machine learning moves fast and has developed its own verification culture—benchmarks, leaderboards, ablation studies. Control theory has different standards. Neither is wrong. But without explicit bridges, the same ideas get rediscovered over and over, dressed in new notation, published in different venues, cited by non-overlapping communities. It’s the Tower of Babel, except everyone thinks they’re speaking the only language that matters.

With compositional tools, you could actually map the translation. “Your attention mechanism is a kernel method. Here’s the functor. Here’s what your benchmark performance implies about the classical bounds. Here’s what the classical theory suggests you try next.” Nobody has to abandon their language. Nobody has to admit they reinvented the wheel. You just build the bridge and walk across it together.

That’s what localized DeSci infrastructure could enable. Not universal protocols that flatten domain differences, but tools that make translation explicit. Everyone keeps their own language. Everyone keeps their own verification standards. And everyone can finally talk to each other without someone storming off to write a BlueSky (clearly superior to x, fight me) thread about how the other field doesn’t understand rigor.

Conclusion

The atoms of knowledge aren’t universal because the atoms of causation aren’t universal. Higher-level descriptions can carry more causal information than lower-level ones. What looks like imprecision at the macro level might actually be the right grain for the causal structure you’re working with.

Stuart Kaufmann’s ideas about locality is exactly what makes bridging work. Each scientific domain has spent decades developing verification structures tuned to its own causal grain. Those structures are coherent—they work for what they’re trying to do. When you formalize them on their own terms and then look

for structure-preserving maps between adjacent domains, you’re connecting things that already make sense internally. That’s very different from forcing everything through a universal substrate, which tends to destroy exactly what made each domain’s standards appropriate in the first place. It is the difference between a pruned and a non-pruned network.

What might this look like in practice? A longevity DAO that implements metadata compatible with medical evidence hierarchies, so its findings can actually flow into systematic reviews. A machine learning benchmark that includes explicit mappings to classical statistical theory, so the control theorists don’t have to keep quietly reinventing things in the corner. A cross-disciplinary literature review tool that doesn’t just search keywords but actually maps the compositional structure between fields—showing you that this ecology paper and that economics paper are studying the same dynamical system with different names.

The Langlands program showed mathematics how generative this approach can be. The Topos Institute is building the infrastructure. The collective intelligence work by pol.is shows what bridging looks like when you respect local structure in opinion space, we can do something similar in knowledge space.

The verification protocols across scientific fields aren’t failures to coordinate. They’re adaptations. And that’s precisely why bridges between them might reveal connections that weren’t visible before.